The Productivity Ceiling of AI Coding Tools

Move 10x as fast, break 10x as many things

Intro

I’m sitting at my laptop at 11pm, running Cursor with 4 separate Claude Code conversations happening. I feel more productive than I’ve ever been. But I’d like to go to sleep soon, and unless I keep sitting here, actively prompting and reviewing, no work gets done.

We’re already at an early inflection point of modern AI coding tools. You can knock out features in an hour instead of a day, or brainstorm and refine much more quickly and comprehensively. But your productivity is constrained by your capacity for attention, and it’s not always clear whether you’re actually getting more done or just starting more things you never finish.

A very relatable Exhibit A:

Over the past few months, I’ve helped a few clients explore different approaches to effectively integrate AI coding tools into their development workflows. In most cases, it feels like we’re improving productivity, which is cool, but feels like we’re not pushing hard enough. What if our target was to maximize productivity?

I wondered: what if I could define 20 tasks, fire them off in the background, go to sleep, and check their status when I wake up?

That question led me to build GZA.

Requirements, From Beautiful To Specific

I started with a simple vision of a beautiful world:

Define a bunch of tasks

Run them in the background

Do something else for a while, like sleep, exercise, attend a meeting, or stare out the window

Check back later for the results

But once I started thinking through the details, the requirements hardened:

Tasks as prompts. No formal format or PRDs required. I wanted to express work the same way I’d express it to Claude Code directly. Vague prompts might produce vague results, but that’s fine — I can iterate.

Asynchronous execution. Work happens in the background with logs I can review later. I remove myself as the real-time bottleneck.

Git branch isolation. Every task gets its own branch. I can merge them, improve them, or throw them away.

Execution isolation and safety. Agents should run in contained environments such as Docker where they can’t accidentally detonate my local machine.

Agent flexibility. My initial target agent/model was Claude Code, but that can evolve. Different agents for different task types should be possible.

Cost consciousness. I don’t want to unknowingly run a poorly-defined task for hours and waste a bunch of money. I want to aggressively limit conversation length, then optimize if it’s not resolving within an acceptable timeframe.

The Cutting Edge

I currently use Cursor with Claude Code, sometimes Cursor chat, sometimes VSCode with Claude Code. All of these options are excellent, but are designed for synchronous, human-in-the-loop workflows.

Here are other tools I researched:

opencode and aider both look good, but have similar workflows to running Claude Code directly.

Amp looks great. The concepts of threads and handoff are interesting, and probably necessary in some form once a certain volume of concurrent or multi-step agent work is happening.

Ralph directly tackles background execution, which is my primary requirement. But I don’t want to require PRDs as input, and I felt the overall approach of “keep working until the queue is empty” wasn’t exactly what I wanted.

Gas Town is fascinating — a fully automated community of agents with different roles. This is way beyond my current goals, but it is probably where a large segment of the industry is heading, whether we see it now or not.

All of these tools looked strong, but none met all my requirements. I needed to learn more details about the problem space. The most educational way forward was to build something, so I dove in.

Initial Sketches

To my memory, the initial version of GZA was a bash script that used a markdown file to store tasks. Once a task was completed, it was prefixed with a checkmark and moved on to the next one. It worked surprisingly well.

But pretty soon I ran into some limitations:

Using markdown for tasks was clumsy, as the file was often updated by the agent as I was editing it to add new tasks, causing confusion and mild data loss.

I moved the tasks to YAML, which allowed me to structure tasks with things like

statusandcompleted_atfields, but the file was soon filled with completed tasks which made it hard to edit.

I migrated from bash to Python and moved task definitions from YAML to SQLite. I’m still not completely sold on using SQLite, but we’ll discuss that later.

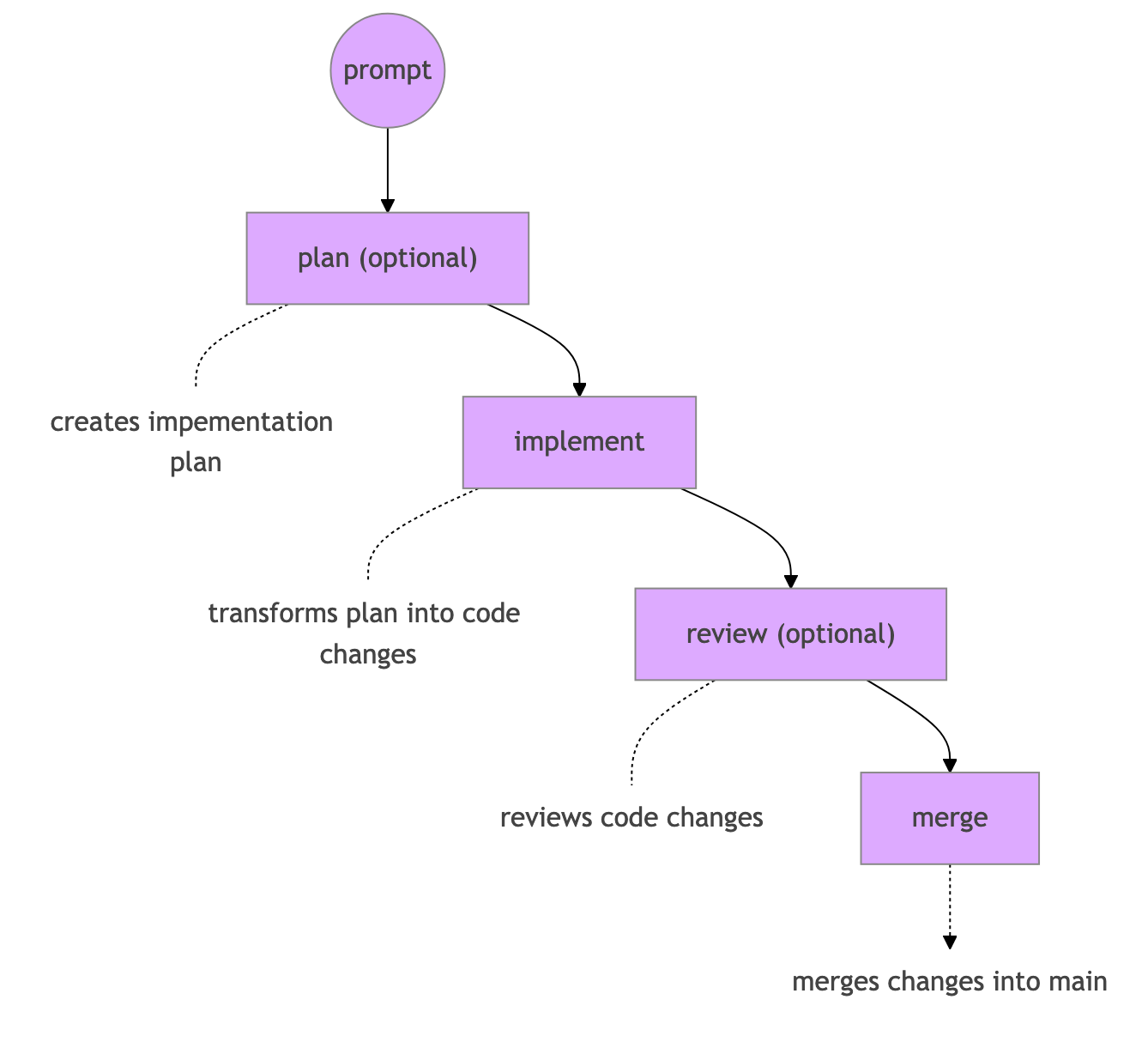

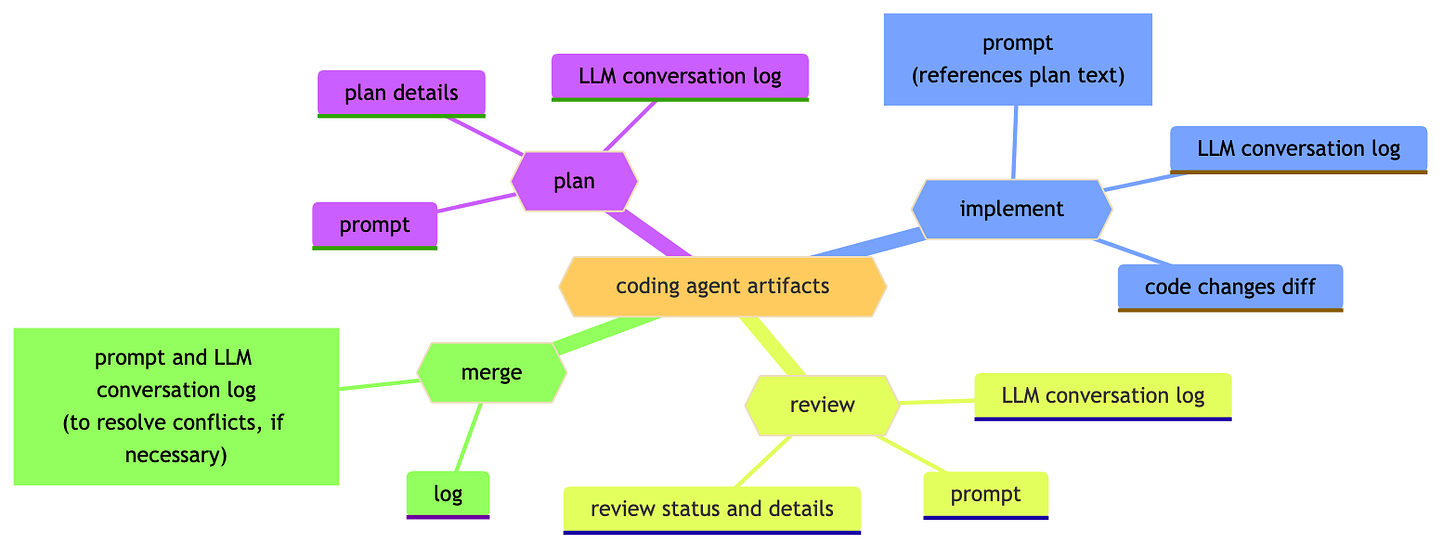

More importantly, a workflow started to emerge. From your initial prompt, you plan (maybe), you implement, you review (maybe), you merge:

Each of these steps is more complex than it seems. Partially because we are automating work that has been performed by humans for decades, but mostly because there are so many moving parts:

Each of these workflow steps turned out to be more complex than expected:

LLM reliability: Connections hang, responses timeout, agents get stuck in conversational loops repeating the same actions

Plan quality: Too vague, too detailed, or just… wrong in other ways

Implementation noise: Unnecessary files created in weird places despite explicit instructions

Review clarity: Feedback that’s too subtle to act on programmatically

Merge conflicts: Increase exponentially as you run more concurrent tasks

Each of these deserves its own post. For now, I’ll just say that GZA handles them through a combination of max turn limits, manual review gates, structured review outputs, and automatic rebasing. It’s not perfect, but it’s functional enough for daily use.

GZA Principles and Usage

First, let me say that this project is very new and rough. Some things probably do not work, especially around failure edge cases. Please file bugs and I’ll fix them, or submit a PR. I’ve built 95% of GZA with GZA — feel free to do the same.

Reading the quickstart is your best bet for getting started. But I’ll summarize here:

# install GZA

uv install gza-agent# initialize config file

uv run gza init# add task prompt (opens $EDITOR)

uv run gza add# run single task (with -b to run in background)

uv run gza work -b# run 5 tasks in background

uv run gza work -c 5 -b# show running tasks

uv run gza ps# view logs for task

uv run gza log 1# view status of task

uv run show log 1# show tasks with unmerged work

uv run gza unmerged# merge task 1 which just completed

uv run gza merge 1I’ll cover details on these features and more in future posts.

The Chaos of Automated Coding

I’ll discuss a few of the bigger things that I’ve learned in building and using GZA over the last few weeks.

Conversational Loops

I asked for a vague feature and there wasn’t enough project context for the agent to move it forward. It went in circles for many turns until it learned the information it needed.

Luckily I had a few things:

The concept of max turns in GZA’s configuration, which stopped the conversation after 50 turns.

A log of the conversation

I then:

Started an interactive Claude Code session

Asked it to look at the log and evaluate why it took so long

Asked it to add that information as project context into

AGENTS.mdRe-ran the task

And it worked much faster this time. This example was me resolving an error, but if you zoom out there is a larger pattern of evaluating how tasks are interpreted, planned and implemented, and finding ways to make that process faster and higher-quality.

To say it another way: this was not just me stepping in to fix a problem. This was me stepping in to improve the system so that similar problems would be much less likely to occur in the future.

Merge Conflicts

I started a bunch of tasks in the background. I then attempted to merge them in order of importance, but that wasn’t the same order they were completed in. I then ran into a few merge conflicts.

The easiest ones were fixable with a simple rebase. This feels easy to automate. I had a client last year with a monorepo in which direct merges were prohibited, so all changes sat in a giant merge queue, usually for minutes, sometimes for hours. 25% of the time, merges would fail, you’d rebase and push your branch, and then they’d succeed. Unpleasant and inefficient.

For merges that a simple rebase can’t fix, I see no reason why we can’t prompt Claude to fix it.

But beyond specific technical problems, using GZA has entirely shifted how I think about my development workflow. Which raises a larger, deeper, more haunting question…

Calibrating Human Involvement

There’s an underlying tension I’ve felt since starting this project: how much I need to be directly involved in the software development of my own projects?

I do not think architectural plans can be fully automated in my world, at least as of yet. But they can certainly be AI-assisted in both the creation and review of the plan.

Coding can definitely be automated.

Code reviews can be automated.

As discussed, merging can be automated.

Deployments have been automated for years, as have error detection, alerts, and other observability angles.

When you zoom out, it doesn’t feel that we are particularly far off from operating the systems that build the systems, and the current situation is just a logical extension of where we were yesterday. The technology just had to leap over a few final hurdles.

If I had to summarize, I’d say: the level of human involvement is now a personal and/or organizational choice, not a technical one.

In the Gas Town article I linked earlier, Steve Yegge mentions stages of AI-assisted coding, with Stage 1 being “Zero AI” and Stage 8 being “Building your own orchestrator.”

I, a solo consultant, am somewhere between Stages 5 and 8 in my personal work, and for clients, I operate as boldly as I can within their environment.

But for you? The choice is yours.

What’s Next?

I’ve learned a lot building this very early version of GZA, and I’m already using it daily for my development work. It’s rough, but fun and functional.

I’m planning future posts on specific problems and solutions I’ve found, such as:

Using Docker to isolate agent execution

Automated code reviews and iterations

Automated merge conflict resolution

Handling nested tasks and interruptions

If you’re thinking about how to effectively integrate AI coding tools into your team’s workflow, feel free to reach out. I’m working with a handful of companies on exactly this.

Thanks for reading and have a wonderful day.

if you enjoyed this article, you’ll also enjoy my book:

PUSH TO PROD OR DIE TRYING: High-Scale Systems, Production Incidents, and Big Tech Chaos

A book filled with lessons that AI can’t replicate… for now.

Spot on. The 'babysitting' problem is indeed the biggest bottleneck to AI adoption in engineering workflows. Moving from AI as an autocomplete to a truly autonomous agent requires better context injection and robust feedback loops. For those looking for tools specifically designed to help agents understand complex architectural contexts with less supervision, https://open-code.ai is exploring some very interesting solutions in this space. Great insights!

You've highlighted a lot of the conversations I've been having with myself lately. That is where I am right now: 2-3 agents working on independent git worktrees, with me checking in when they reach a stopping point. Then there is a future I know exists: 10+ agents working, some on semi-autonomous tasks that still require my input, and some on small, completely autonomous tasks. Much of my time lately has been spent mapping how to get there and also fixing the spectacular ways I've failed to get there.

However, just over the last 6-8 weeks, I've gone from thinking the 10+ agent future is impossible and dumb to not only possible but desirable. Even as overall capability growth in the underlying models is slowing down, it feels like the change to our workflow is speeding up. I'm not sure if it's finally grappling with how to use the models or if there was some small threshold they needed to hit. Opus's ability to choose the correct tools in the correct circumstances has been a particular boon.